Quercus coccinea Muenchh. - Scarlet Oak

Common Names

Scarlet OakField Identification

Large deciduous tree with alternate, simple, lobed leaves; with pendant catkin-like flowers in early summer followed by acorns in the fall.Medicinal uses

Disclaimer: The information provided here is for reference and historical use. We do not recommend nor do we condone the use of this species for medicinal purposes without first consulting a physician.

Used by Native Americans to treat a variety of maladies including dysentery, indigestion, mouth sores, chapped skin, fevers, asthma, and urinary tract disorders. (Moerman, 1998)

Other uses

Oak-mast surveys may help wildlife agencies better understand dynamics of fall harvests and may be useful in harvest management models that attempt to stabilize fall harvest rates of game animals (Norman, 2003).Tannins derived from oaks have been used historically to tan animal hides into leather. (Burrows & Tyrl, 2001)

Poisonous Properties

Oak leaves, buds, bark, and acorns contain tannins which have varying degrees of toxicity in different animals. Although oak foliage and acorns provide valuable food for many wildlife species and even some livestock, oak toxicosis, a urinary and digestive tract disease can occur when some animals are forced to subsist on oaks exclusively for several days. Poisoning is rare in humans due to the large amounts needed to ingest to cause symptoms. (Burrows & Tyrl, 2001)

Stories

Dryads (or "tree spirits") are nymphs associated with Greek mythology which live near, or in, trees. Dryads are born bonded to a specific tree, originally, in the Indo-European Celtic-Druidic culture, an oak tree. Drys in Greek signifies 'oak,' from an Indo-European root *derew(o)- 'tree' or 'wood.' In the primitive times, the Greeks imagined, people were able to live on acorns.

Nomenclature

Quercus coccinea Munchh., Hausvater 5(1): 254. 1770.?Quercus rubra var. coccinea Ait., Hort. Kew. 3: 357. 1789.

Quercus acuta Raf., Alsogr. Am. 22. 1838.

Quercus coccinea var. rugelii A. de Cand., Prodr. 16,2: 62. 1864.

Quercus coccinea var. vulgaris Vasey, Am. Entomologist 2: 344, f. 212. 1870.

TYPE: Unknown

Description

HABIT Perennial, deciduous, phanerophytic, tree, diclinous and monoecious, 25-30 m tall.

STEMS Main stems ascending or erect, round. Bark tightly and irregularly fissured with scaly ridges, dark brown or dark gray, not exfoliating. Branches erect or ascending or horizontal. Twigs dark reddish-brown on 1st year, grey to brown on older twigs, fluted-terete, 2-5 mm in diameter, smooth and lenticellate, glabrous. Pith white, 5-pointed, continuous, nodal diaphragm absent. Sap translucent. For an anatomical study of the xylem see Williams, 1939.

BUDS Terminal and axillary present, clustered at twig apices and scattered along stem, usually hairy on distal half only. Terminal bud ovoid, blunt; axillary buds ovoid, blunt. Bud scales dark brown or brown (distal margins darker-colored), imbricate, with short and unbranched appressed brown or light brown or white hairs, sparsely or moderately densely distributed. Bud scale scars encircling the twig. Leaf scars crescent-shaped. Vascular bundle scars numerous, scattered.

LEAVES Alternate, simple, (appearing pseudo-opposite or pseudo-whorled at twig apices), crowded toward stem apex or spaced somewhat evenly along and divergent from stem. Stipules lateral, free from the petiole, linear, caducous. Petiole adaxially flattened, 2-6 cm long, glabrous. For an anatomical study of the petiole abscission region see Hoshaw & Guard, 1949. Leaf blades: abaxial surface light green, glossy; adaxial surface green, glossy; elliptic or ovate or obovate, bilaterally symmetric, 7-15 cm long, 7-15 cm wide, chartaceous; base obtuse or truncate; margins somewhat symmetrically 2-3(4) lobed per side 1/2 - 7/8 distance to the midvein with rounded sinuses and acute, aristate apices; apex acute and aristate. Abaxial surface obscurely papillose and glabrous except for tufts of fasciculate erect to spreading brown hairs, distributed in the main vein axils. Adaxial surface glabrous. Other types of hairs (multi-cellular bulbous, unicellular solitary) present on immature leaves only, see Hardin, 1979a;Thompson & Mohlenbrock, 1979; and for an overview of the phenology and the variability and density of hairs due to ecological factors and hybridization see Hardin, 1979b. For an anatomical study of the stomata, cuticle and mesophyll in relation to different light environments see Ashton & Berlyn, 1994.

FEMALE INFLORESCENCES Coetaneous, spike consisting of a single flower (sometimes 2-3), in axils of current year leaves, subsessile initially, often becoming short-pedunculate in fruit, surrounded by a cupule which is persistent, accrescent, and indurate in fruit (acorn cap). There has been debate over the years regarding the true ontogenetic nature of the cupule. Originally thought to be an involucre of bracts, recent research suggests that the cupule is a complex partial inflorescence derived from stem tissue, see Abbe, 1974;Brett, 1964;Foreman, 1966;MacDonald, 1979;Fey & Endress, 1983. Each cupule subtended by 3 minute, caducous bracteoles.

FEMALE FLOWERS Perianth of one whorl, minute, fragrance absent. Calyx urceolate, of fused sepals. Carpels 3. Locules 3, each containing 2 ovules. Styles 3, each with 1 stigma. Ovary inferior. Placentation axile. For an investigation of embryogenesis see Stairs, 1964.

MALE INFLORESCENCES Coetaneous, compound, solitary or fascicled spikes; pendant, catkin-like; in leaf axils of previous year. Rachis moderately covered with brown to white hairs; elongating and glabrescent with age; with 1 subsessile or sessile flower per node, each flower subtended by a small, sessile caducous bracteole.

MALE FLOWERS Perianth of one whorl, 3.5-4 mm in diameter, fragrance absent. Calyx actinomorphic, campanulate, of fused sepals. Sepal lobes 5-6, broadly oval to ovate with brown to white hairs moderately dense along margins. Stamens 4-5, exserted. Anthers glabrous, basifixed, opening along the long axis. Filaments free, 1mm long, straight, glabrous (Solomon, 1983a).

FRUIT

Acorn (glans (Kaul, 1985)) sessile to short-pedunculate; maturation biennial.ovoid-oblong, 2-2.5 cm long, comprised of 2 parts- a. the turbinate cup (cupule), enclosing 1/2(1/3?) of the base of the nut; and b. the nut, 1-seeded by abortion (for a hypothesis that the first ovule fertilized suppresses the normal development of the others see Mogensen, 1975). Cupule exterior composed of imbricate, moderately appressed glossy scales sparsely covered with brown tomentum. (Q. coccinea var. tuberculata Sarg. with scales thickened below the middle, those of the upper row thin and forming a distinct marginal ring (Sargent, 1918)). Nut olive-green to brown, ovoid-oblong (subglobose?), with large light-colored circular cupule scar at base and apiculate at the distal end; minutely laterally striate; initially with minute short and unbranched appressed brown to light brown hairs, sparsely or moderately densely distributed throughout, glabrescent; often with concentric, rugose rings surrounding apiculus. One study found a size range of .52-3.96 cubic cm with a mean of 1.70 cubic cm and a correlation between smaller acorn size with increasing latitude (Aizen & Woodcock, 1992).

SEEDS Embryo with two large fleshy cotyledons, endosperm lacking. (Young & Young, 1992).

Habitat

Usually occurring on mesic to dry well drained substrates in barrens, slopes, ridges, mountain tops, and roadsides, usually in full sun.Distribution

Indigenous to the eastern United States.

United States -- AL, AR, CT, DC, DE, GA, IL, IN, KY, MA, MD, ME, MI, MN, MO, NC, NH, NJ, NY, OH, PA, RI, SC, TN, VA, VT, WI, WV

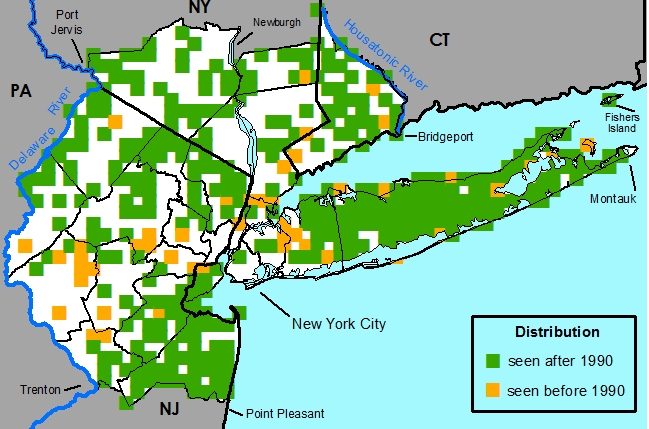

New York Metropolitan Region -- Native throughout the metropolitan region.

Rarity Status

Global Heritage Rank -- G5

Connecticut -- Not listed

New Jersey -- Not listed

New York -- Not listed

Species Biology

Flowering April [week 4] - May [week 4]

Pollination Anemophily

Fruiting August [week 1] - October [week 4]

For a study suggesting that masting is effected by weather in conjunction with inherent reproductive cycles see Sork, et al., 1993.

Dispersal

Small predators of acorns facilitate dispersal by dropping undamaged nuts and failing to recover cached nuts. These include Sciurus carolinensis (gray squirrel), Sciurus niger (fox squirrel), Glaucomys volans (Southern Flying Squirrel), Tamias striatus (eastern chipmunk), Peromyscus leucopus (white-footed mouse), Peromyscus maniculatus (deer mouse), Quiscalus quiscula (common grackle) and Cyanocita cristata (blue jay). (Ivan & Swihart, 2000) (Smith, 1972) (Briggs & Smith, 1989) (Wolff, 1996) (Bosema, 1979) (Darley-Hill & Johnson, 1981) (Johnson & Webb, 1989) (Johnson, et al., 1993) In addition, one study found that many predators preferred the basal end of the acorn and consumed only 30-60% of the cotyledon.

A chemical analyses of acorns from two species revealed that the concentration of protein-precipitable phenolics (primarily tannins) was 12.5% (Q. phellos) and 84.2% (Q. laevis) higher in the apical portion of the seeds where the embryo is located, suggesting that many acorn consumers consistently eat only a portion of the cotyledon of several species of acorns and thereby permit embryo survival. (Steele, et al., 1993).

Probably included in the diet of the grey fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus) (Scott, 1955), eastern wild turkeys (Meleagris gallopavo silvestris) (Norman, 2003), and white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) (Bryant, et al., 1996).

GerminationGeneral rules for collecting and storing acorns: 1. Collect acorns before they lose much water. 2. Ensure acorns are fully hydrated, soak in clean tap water overnight before placing them in storage. 3. Surface dry the acorns just before depositing them in storage to reduce mold growth. 4. Place acorns into cold storage as soon after collection as is possible. (Connor, 2004)

In one study (Q. phellos and Q. laevis), germination experiments revealed equal or greater germination frequencies for partially consumed acorns than for intact acorns. (Steele, et al., 1993).

For a propagation protocol for growing bareroot oaks see Hoss, 2004.